[ad_1]

Since at least the 1818 publication of Frankenstein, our imaginative little human selves have been dreading the moment when our inventions finally get the best of us. In pop culture, stories of technological advancement—and ensuing catastrophe—have endured precisely for their ability to tickle our brains right in that sweet spot where wonder bleeds into horror. Back in the day, we had Mary Shelley and H.G. Wells, Fahrenheit 451 and A Space Odyssey. These days, you can’t make it through civilian-level small talk about our tech-despoiled lives without referencing Black Mirror, The Truman Show, or robot Arnold Schwarzenegger at least once.

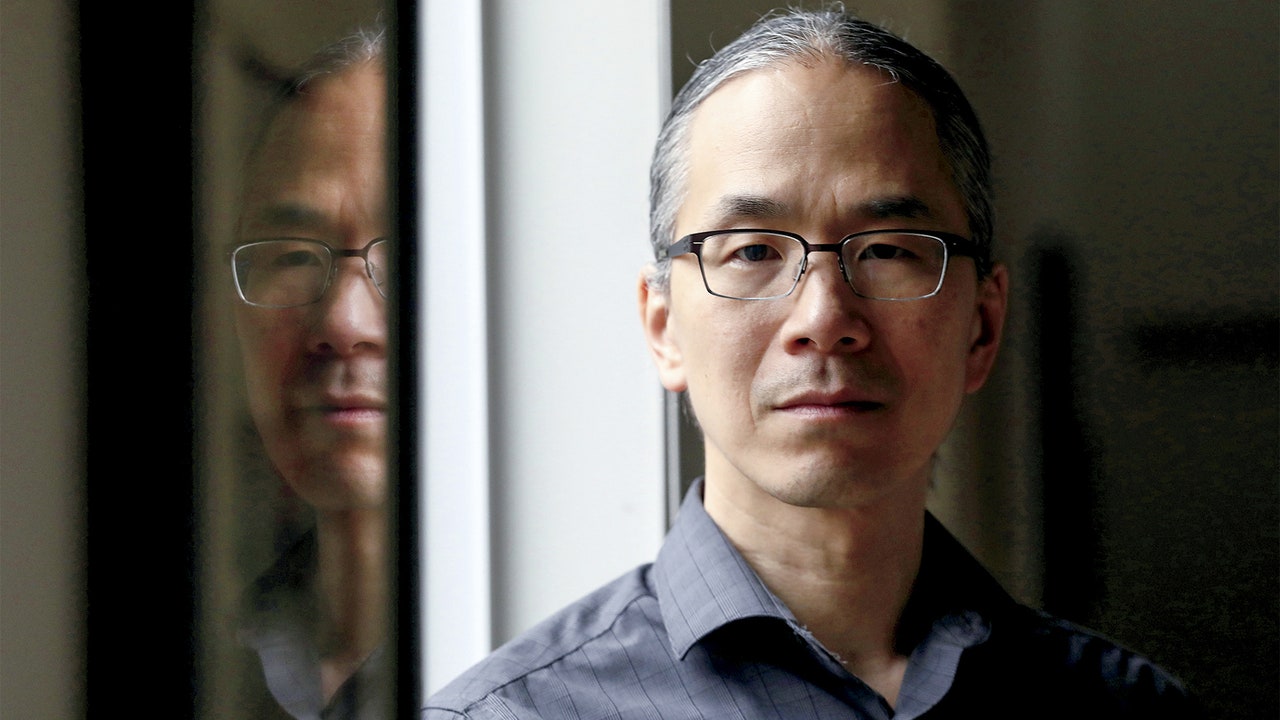

Ted Chiang, author of the most prestigious science fiction of our time (that’s four Hugo awards, four Nebula awards, and one feature film adaptation spread across a measly, by sci-fi standards, oeuvre of a dozen and a half short stories over three decades) understands this human impulse. In Chiang’s fiction, characters across all kinds of universes grapple with the limits of our kind as they claw toward transcendence via automatons and alien languages. In fiction and in life, we humans like to think we can see it coming.

Lately, Chiang has been thinking about this current reality: Via viral essays for The New Yorker, he’s been wading into this year’s public discourse to explain ChatGPT and generative AI in terms any smartphone-wielder can actually process. For a species forever at odds with our own imaginative powers, the sci-fi author has become the most lucid voice in the room—a credit as much to that compact Chiangian prose as much as it is to the utter chaos of the 2023 technological landscape.

Some time in between Marc Andreessen blogging about how AI will save the world and the release of the new Black Mirror season, Chiang and I sat down over Zoom to discuss our current moment in tech and the metaphors we use to make sense of it all.

This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Vanity Fair: In terms of cultural touchstones, what were your earliest influences?

Ted Chiang: When I was maybe 11, I started reading Isaac Asimov—his science fiction and his popular science writing. Reading both gave me a very clear sense of the difference between the two. When I was younger, say in fourth grade, I had been really into books about sea serpents and Bigfoot and ancient astronauts. What I didn’t realize was the mixture of fact and fiction that is involved in those topics, so when I started reading Asimov, it clarified for me the nature of my interest. Because, yeah, there’s cool stuff in science, and there’s really cool stuff in speculating about science, but in coming up with your fictional scenarios inspired by science, you should be very clear about which one you’re engaged with at any point.

You started writing and submitting short stories in high school. Do you still recall the first one you sent out?

It was an adventure story set in space, about a rescue attempt of a ship that was marooned. I did a ridiculous amount of research for it—I remember looking up “What is the wavelength of gamma radiation from electron positron collisions?”

Over your career in sci-fi, your batting average is rather legendary in terms of your story to awards ratio and acclaim. Did you know you’re referenced in the latest season of Netflix’s You?

I’ve been made aware.

Is there one single award or honor you’ve received that stands out to you? Like, which Hugo meant the most?

I don’t think I have a good answer for that. It’s been a long string of totally unexpected events.

How plugged in are you to the daily churn of tech news? I’m curious if you keep up with things like Marc Andreessen’s blog post about AI.

I am not, although I guess I’ll say I’m not super interested in what Marc Andreessen has to say. In general, I can’t say that I really keep up in any systematic fashion. But nowadays, you almost have to make a deliberate effort to avoid hearing about AI.

Would you consider yourself to be an early adopter?

Not of most technologies. I feel like being an early adopter requires a real commitment to constantly getting used to a new UI. I’m interested to see what is happening in technology, but in terms of my day-to-day work, I’m not looking for new software unless there’s an actual problem that I’m having. I wish I could still use a much older version of Word than I have to.

How did your relationship with The New Yorker come about? The first couple of things you wrote for them back in 2016 and 2017 weren’t about tech per se. Who put it together that you should do those AI explainers?

[ad_2]

Source link