[ad_1]

As patients, we only see one dimension of a doctor’s job. They examine us, sometimes perform a procedure, give us a treatment plan, maybe refer us to a colleague. But for doctors, interacting with patients is just one part of their work. They also deal with insurance claims, enter patient records electronically, consult previous records. And they take notes—lots and lots of notes.

Doctors take notes for everything related to a treatment:

patient history, diagnosis, insurance, second opinions. Notes are essential—and time-consuming. In the US, doctors spend two hours completing administrative tasks for every hour with a patient, according to one study. It’s a burden that contributes significantly to the high levels of burnout in the profession.

Now imagine if someone or something else could take all those notes—whether on a patient’s history, diagnoses, insurance plans, second opinions—and then organize them and make sense of them, freeing doctors from the task.

In fact, it’s already happening, with artificial intelligence for medical note-taking.

Most Americans are uncomfortable with the idea of having AI in their doctor’s office, the Pew Research Center found last year. Well, too bad. Such AI tools can already be found in tens of thousands of doctors offices around the US.

How does AI work in healthcare?

There are many ways AI can be (and is) employed in healthcare. Doctors use it for imaging-based breast cancer detection, to treat strokes and detect cardiovascular disease, and to assist surgical robots. Now it can support physicians during patient visits too, thanks to generative AI.

The premise is simple. During a visit, an AI tool listens in on everything that happens—the patient’s complaints, the doctor’s comments. It then transcribes the exchange, like normal voice recognition or transcription software would, but it does something more: It transforms the information into a well-organized document ready to be imported to the patient’s electronic health record (EHR), sent to insurance providers, or shared with other physicians.

This is the kind of work that doctors and nurses hardly have time to get to during their regular working hours and often take home, organizing and updating their notes and forms while dinner is cooking, or after the kids are in bed. It eats away at what little time off they have, and at their mental health, compiling the burnout and stress commonly found in the healthcare professions.

“Physicians, they love to care for patients and they hate what they call ‘pajama time,’” said Alexandre Lebrun, co-founder of Nabla, an AI clinical note-taking software startup based in Paris. Nabla is integrated with OpenAI’s GPT-4, a large language model capable of generating human-sounding prose. A couple of months ago, Nabla launched Copilot, a Chrome browser extension that works with audio input, transcribing a doctor’s visit and turning it into notes.

“A game changer”

“It’s a game changer,” said James Schwartz, a physician for the county jail in Naples, Florida, who uses Nabla’s tool. Schwartz has worked as a doctor since the 1990s, practicing family medicine in Rhode Island for more than two decades before moving to Florida. For just as long, he’s wished he could do away with taking notes. “We all recognize that note-taking is critical, but it’s also not what we went to medical school for,” he says.

That desire to dispense with bulky paper notes turned Schwartz into an early adopter of electronic medical records and later of transcription software. But he became disillusioned with the direction that EHR was taking, focusing much more on the collection of patient data than on the support for clinicians’ work, and on easing the burden of administrative tasks.

“I wish there was a supercomputer that could listen in on the clinical encounter and then synthesize a clinical encounter,” Schwartz remembered thinking. “Essentially, I rubbed a genie lamp 15 to 20 years ago, and finally it granted me my wish,” he said of Nabla’s tool.

Besides handling notes, the program allows Schwartz to have a better setup for visits so he can give patients his undivided attention, without looking at a monitor or typing. He wears a lapel microphone, he said, moving between prison cells with a rolling desk a few feet behind him.

“Then when I’m finished with my rounds, I just look at all my notes and copy and paste them and do everything that’s required,” Schwartz added. “To my surprise, actually, I thought the generator would hallucinate more, but it really doesn’t.”

The kind of support the AI tool provides him would have had a tremendous impact on his career, Schwartz maintained. “I wouldn’t have taken my work home with me at night to finish my notes. For one thing, I would have been able to continue rounding on my patients in the hospital,” he said. “And overall, it would have been a much less stressful career.”

Trust the machine—to a point

Less than three months after its launch in early spring, Nabla only has 800 users, though its client base is growing 10% to 20% a month, according to Lebrun and Delphine Groll, his co-founder. But a host of other companies provide software for clinical note-taking, including Nuance, the maker of Dragon Ambient eXperience, and DAX, the market leader, used by more than half a million doctors in the US.

Unlike Nabla’s product, DAX doesn’t—or doesn’t yet—deliver notes in real time. Yet for doctors, the perceived benefits of using even a slower note-taking system are huge, including higher retention in a field with severe staffing shortages. “Everyone should want that, because that reduces the burden on the doctor, it allows them to see more patients, it reduces paperwork—and your wait time to get into your primary care or urgent care [center] would go down, theoretically,” said Marc Succi, a radiologist and a chair of innovation and commercialization at Mass General, Brigham Enterprise Hospital.

Succi, who has done research on incorporating AI into the clinician workflow, says the provider still needs to review and sign off the notes, because the AI can be inaccurate. “I don’t think I would feel comfortable using transcription software and simply not reading what it wrote,” he said. “You could imagine it could misinterpret things.

This is where AI might fall short of expectations for the potential to create drastic workload reductions, said Dev Dash, an AI researcher at the Stanford University School of Medicine. “Sometimes in clinical practice, it’s a lot easier to generate a note yourself than to rely on an AI tool and have to review the entire note,” he said. “That becomes truer the longer the note is.”

In other words, reviewing notes generated by AI could be as burdensome, or even more so, than writing the note yourself.

AI for diagnostic support

But with AI’s note-taking skills already hitting new levels of complexity and accuracy, it’s getting easier to conceive of a time when generative AI will get involved in other medical tasks, like clinical decision support. In fact, the first companies experimenting with some level of diagnostic support are already here.

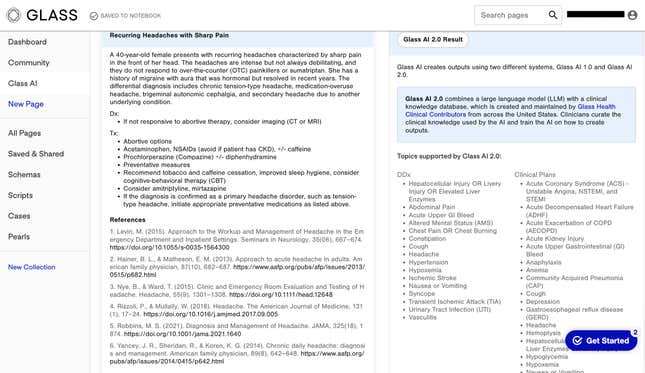

One is Glass Health, a Silicon Valley startup that uses large language models to compile medical knowledge and assist doctors with their diagnoses and clinical plans. Using the software, a healthcare practitioner can input a paragraph describing the patient and any symptoms, and receive a tentative diagnosis or treatment plan along with references to relevant articles and medical literature.

This doesn’t mean the AI performs a doctor’s job. “Our AI is an assistant to doctors. It does not replace doctors in any kind of way. It doesn’t replace clinician judgment,” said Dereck Paul, co-founder and CEO of Glass Health, who was inspired to build the support tool after being an internal medicine resident during covid, when he experienced firsthand the limited resources available to physicians. “It’s something that you want clinicians to think of on the level of a trainee…an assistant that can make suggestions and might help you think about something you weren’t thinking about before.”

With 40 academic clinicians training the model to deliver more accurate diagnoses and treatment plans, and tens of thousands of users already, Glass Health hopes to become the ultimate repository of medical knowledge, eventually helping doctors to diagnose complex issues.

“This is the kind of team that maybe 10 years ago would be working on an online textbook for medicine and 20 years ago would have been writing paper textbooks,” Paul said. “But that team of experts is now training on how to assist doctors with a machine.”

What about the need for humanity in healthcare?

As the industry reckons with new applications for AI, there are some in the field who worry the technology will replace essential parts of the care process. Among them is Emily Silverman, a doctor at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and founder of The Nocturnists, which produces podcasts and live events promoting storytelling by healthcare workers.

“For me, writing notes is an important time for quiet thinking,” Silverman says. “I work in the hospital, where patients are acutely sick and complex with multiple disease processes. I often arrive at my diagnosis and treatment plan in the process of externalizing my thoughts on the page. So I’m not sure how an AI tool would fit into that process.”

Silverman is fine with outsourcing mindless administrative tasks, but she’s troubled by the lack of humanity she finds in AI-generated clinical notes. “I can tell which sections were written by humans and which weren’t.”

The human sections have their own voice, Silverman says, which makes reading medical records much more pleasant and keeps clinicians alert to important information. “I’m worried about the physician voice becoming further homogenized by AI and my eyes just glazing over as I’m trying to read notes and understand who patients are,” she says.

But as AI bots get more sophisticated—that is to say, more human-like—concerns like those may start to disappear, if only to make room for worries about the next areas of medicine where AI intervenes.

[ad_2]

Source link