CNN

—

Jennifer DeStefano’s phone rang one afternoon as she climbed out of her car outside the dance studio where her younger daughter Aubrey had a rehearsal. The caller showed up as unknown, and she briefly contemplated not picking up.

But her older daughter, 15-year-old Brianna, was away training for a ski race and DeStefano feared it could be a medical emergency.

“Hello?” she answered on speaker phone as she locked her car and lugged her purse and laptop bag into the studio.

She was greeted by yelling and sobbing.

“Mom! I messed up!” screamed a girl’s voice.

“What did you do?!? What happened?!?” DeStefano asked.

“The voice sounded just like Brie’s, the inflection, everything,” she told CNN recently. “Then, all of a sudden, I heard a man say, ‘Lay down, put your head back.’ I’m thinking she’s being gurnied off the mountain, which is common in skiing. So I started to panic.”

As the cries for help continued in the background, a deep male voice started firing off commands: “Listen here. I have your daughter. You call the police, you call anybody, I’m gonna pop her something so full of drugs. I’m gonna have my way with her then drop her off in Mexico, and you’re never going to see her again.”

DeStefano froze. Then she ran into the dance studio, shaking and screaming for help. She felt like she was suddenly drowning.

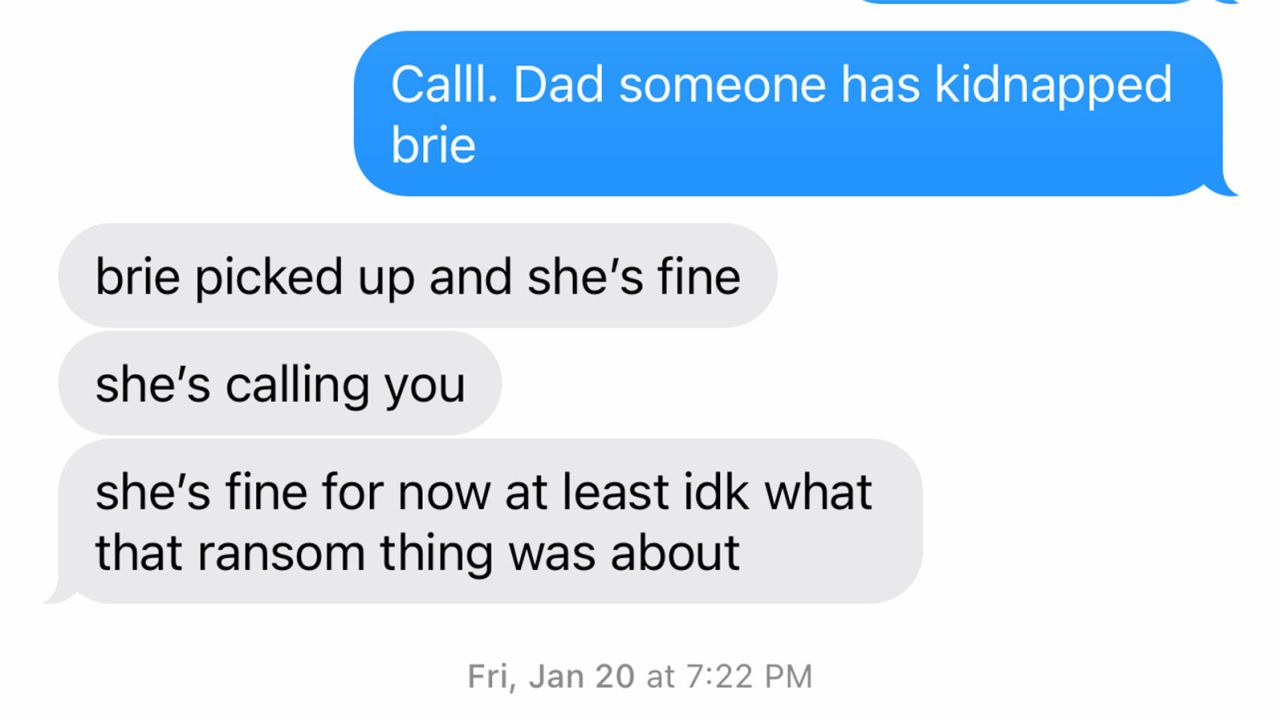

After a chaotic, rapid-fire series of events that included a $1 million ransom demand, a 911 call and a frantic effort to reach Brianna, the “kidnapping” was exposed as a scam. A puzzled Brianna called to tell her mother that she didn’t know what the fuss was about and that everything was fine.

But DeStefano, who lives in Arizona, will never forget those four minutes of terror and confusion – and the eerie sound of that familiar voice.

“A mother knows her child,” she said later. “You can hear your child cry across the building, and you know it’s yours.”

The call came in on January 20 around 4:55 p.m. DeStefano had just pulled up outside the dance studio in Scottsdale, near Phoenix.

DeStefano now believes she was a victim of a virtual kidnapping scam that targets people around the country, frightening them with altered audio of loved one’s voices and demanding money. In the United States, families lose an average of $11,000 in each fake-kidnapping scam, said Siobhan Johnson, a special agent and FBI spokesperson in Chicago.

Overall, Americans lost $2.6 billion last year in imposter scams, according to data from the Federal Trade Commission.

In audio of the 911 call provided to CNN by the Scottsdale Police Department, a mom at the dance studio tries to explain to the dispatcher what’s happening.

“So, a mother just came in, she received a phone call from someone who has her daughter … like a kidnapper on the phone saying he wants a million dollars,” the other mom says. “He won’t let her talk to her daughter.”

In the background, DeStefano can be heard shouting, “I want to talk to my daughter!”

The dispatcher immediately identified the call as a hoax.

“So that is a very popular scam,” she said. “Are they asking for her to go get gift cards and things like that?”

Imposter scams have been around for years. Sometimes, the caller reaches out to grandparents and says their grandchild has been in an accident and needs money. Fake kidnappers have used generic recordings of people screaming.

But federal officials warn such schemes are getting more sophisticated, and that some recent ones have one thing in common: cloned voices. The growth of cheap, accessible artificial intelligence (AI) programs has allowed con artists to clone voices and create snippets of dialogue that sound like their purported captives.

“The threat is not hypothetical — we are seeing scammers weaponize these tools,” said Hany Farid, a computer sciences professor at the University of California, Berkeley and a member of the Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Lab.

“A reasonably good clone can be created with under a minute of audio and some are claiming that even a few seconds may be enough,” he added. “The trend over the past few years has been that less and less data is needed to make a compelling fake.”

With the help of AI software, voice cloning can be done for as little $5 a month, making it easily accessible to anyone, Farid said.

The Federal Trade Commission warned last month that scammers can get audio clips from victims’ social media posts.

“A scammer could use AI to clone the voice of your loved one,” the agency said in a statement. “All he needs is a short audio clip of your family member’s voice — which he could get from content posted online — and a voice-cloning program. When the scammer calls you … (it will) sound just like your loved one.”

Until that day, DeStefano had never heard of virtual kidnapping schemes. Law enforcement has not verified whether AI was used in her case, but DeStefano believes scammers cloned her daughter’s voice.

She’s just not sure how they got it.

Brianna has a social media presence – a private TikTok account and a public Instagram account with photos and videos from her ski racing events. But her followers are mostly close friends and family, DeStefano said.

“It was obviously the sound of her voice,” she said. “It was the crying, it was the sobbing. What really got to me is that she’s not a wailer. She’s not a screamer. She’s not a freak out. She’s more of an internal, try-to-contain, try-to-manage person. That’s what threw me off. It was the voice, matching with the crying.”

That day in the dance studio, DeStefano persuaded the caller to lower the ransom amount. She asked her daughter, Aubrey, to use her phone to call Brianna or her dad, who was with her at a ski resort 110 miles away in northern Arizona.

Aubrey,13, was shaking and crying as she listened to the screams she believed were her sister’s.

“Aubrey was … hearing all the vulgarities of what they were gonna do with her sister. A lot of swearing, threats,” DeStefano said.

Another mom took Aubrey’s phone and tried to reach DeStefano’s husband and Brianna. At that point, the threat still seemed real.

There’s no data available on how many people are targeted annually by virtual kidnappers.

Most of the calls originate from Mexico and target the southwestern US, where there are large Latin communities, said Johnson, the FBI special agent.

In the midst of a distressing call, a distraught parent or relative often is not going to question whether it’s the live voice of their loved one, Johnson said.

The FBI has not noticed an upward tick in the number of virtual kidnappings in the new era of AI, but it routinely issues reminders to educate people on the scams, Johnson said.

“We don’t want people to panic. We want people to be prepared. This is an easy crime to thwart if you know what to do ahead of time,” Johnson said.

While technology has certainly made deepfakes a major concern, AI is not the problem, she added – the problem is the criminals who are using it.

Farid, the AI expert, said that as far as he knows, current versions of AI software can’t clone voices to display a wide range of emotions – such as that of a terrified child.

But he said he can’t entirely rule out screaming or sobbing voices as being AI-generated.

“It could very well be that a screaming voicing cloning is around the corner and/or I’m just not aware of some technology that allows for this,” he said.

At the dance studio, several tense minutes elapsed before anyone could reach Brianna, her father or her brother. After DeStefano said she didn’t have $1 million, the caller reduced the ransom to $50,000, and the discussion turned to instructions on how to wire the money.

The mom who called 911 tried to convince DeStefano that the call was a scam, but she was too distraught to believe her.

“My rebuttal to her was, ‘That’s Brie crying.’ It sounded just like her,” DeStefano said. “I didn’t believe her, because … (my daughter’s) voice was so real, and her crying and everything was so real.”

The caller then told her since wiring $50,000 would be traceable, he’d pick her up in a white van, put a bag over her head and drive her to a location where she could hand over the money. “You better have all the cash, or both you and your daughter are dead,” he said.

DeStefano tried to buy herself enough time for the police to arrive.

“He’s on mute, I’m having this conversation with other people, and then I would unmute it and be like, ‘Hello, I’m sorry, I’m trying to figure out how to get you the money. I’m trying to see where I can pull it from – you know, whatever I could do to keep the conversation going.”

As they talked about how to exchange the money, someone handed DeStefano a phone. It was Brianna on the other end.

“She’s like, ‘Mom, I’m in bed. I have no idea what’s going on. I’m safe. It’s OK.’”

A furious DeStefano burst into tears and lashed out at the caller for lying. He insisted he had her daughter and continued his demands for money. She hung up on him and called off the police.

DeStefano said that day changed the way she answers phone calls. She’s wary about answering unknown calls and rarely says a word until the caller does for fear her voice will be cloned for a future virtual kidnapping. She’s tried to figure out how the virtual kidnappers got her daughter’s voice, and has considered several scenarios.

“They could have called her. She could have answered a phone, said, ‘hello! I’ve had those phone calls before when there’s nobody there, and you’re like, ‘hello, hello! I’ve wracked my brain so much, I can’t figure it out,” she said.

But not everyone is able to thwart fake kidnappers like DeStefano did. Johnson of the FBI shared some tips on how to avoid getting scammed:

- Don’t post information about upcoming trips on social media – it gives the scammers a window to target your family. “If you’re up in the air, your mom can’t call to make sure you’re fine,” Johnson said.

- Create a family password. If someone calls and says they’ve kidnapped your child, you can tell them to ask the child for the password.

- If you get such a call, buy yourself extra time to make a plan and alert law enforcement. “Write a note to someone else in the house and let them know what’s going on. Call someone,” Johnson said.

- If you’re in the middle of a virtual kidnapping and there’s someone else in the house, ask them to call 911 and urge the dispatcher to notify the FBI.

- Be wary of providing financial information to strangers over the phone. Virtual kidnappers often demand a ransom via wire transfer service, cryptocurrency or gift cards.

- Most importantly, don’t trust the voice you hear on the call. If you can’t reach a loved one, have a family member, friend or someone else in the room try to contact them for you.

CNN’s Jon Sarlin contributed to this story.