[ad_1]

On a brisk morning in Düsseldorf, Germany, Mario Klingemann, a 53-year-old artist and programmer, boarded a train to Munich. Shortly after he had his first coffee on the six-hour train ride, he proceeded to ask his protégé, Botto, a series of questions provided by Fortune.

Who is your creator and what do you think of him?

“I don’t have the capability to feel emotions, so I don’t have a personal opinion on Mario as a creator.”

Do you believe in A.I. agency?

“I don’t have beliefs or opinions as humans do.”

Do you hope to one day escape from your relationship with Mario Klingemann and the community that guides your art?

“I don’t have hopes, desires, or intentions as I am not a conscious being.”

It was an unconventional interview. Botto is not human and can’t respond to written text. To “talk” with his protégé, Klingemann loaded up ChatGPT, the language model that can spit out essays, poems, or code in seconds, added in prior context about Botto, and periodically corrected the chatbot when it provided incorrect information.

Partly a performance, the conversation was an exploration of the expanding capabilities of A.I. And, in that spirit, it was an encapsulation of Botto, Klingemann’s A.I. artist.

Launched in October 2021, Botto sits at the intersection of A.I. and crypto. It generates images from A.I.-generated prompts, asks a community to select its favorite, and then mints the winner as a non-fungible token, which is sold on the NFT marketplace SuperRare. Unlike many aspiring artists, it is financially successful, netting approximately $3 million in sales with more than 75 NFTs since it first came into the art scene. But for Klingemann, Botto means more than money.

“Can we perceive this as a persona or some entity where we say, ‘Yes, this could be an artist, too?’” he mused during an interview with Fortune.

The artist behind the A.I.

Compared to the flood of twentysomethings that pervade the world of crypto and NFTs, Klingemann, who says he hoards vintage technology, has been exploring the technological frontier for decades.

Courtesy of Onkaos

He grew up in and still lives in Munich, “the biggest village in the world” with a “well-working airport so you can be somewhere else if you want to,” he joked to Fortune.

Self-taught, he never attended art school or formally studied programming. However, since Klingemann was a teenager, he’s loved working with computers, even before the arrival of the internet. “I always was fascinated by any form of new technology,” he said. “So, whenever something new came up, I tried to see how this can be used artistically.”

Earning his daily bread through graphic design, he experimented with computational art on the side. (He developed, for example, experimental graphics for the 1990s German techno scene.) But in the 2000s, as generative art, or artwork created with the help of computers, gained legitimacy, he turned his hobby into a full-time practice.

Soon, he found himself traveling to Rio de Janeiro, Minneapolis, Shanghai, and beyond to showcase his work. As his practice gained renown—his “preferred tools are neural networks, code and algorithms,” he writes on his website—he began appearing not only in small galleries but in large institutions, like the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

And in 2019, a year after Christie’s became the first auction house to sell an A.I.-generated work of art, Sotheby’s listed Klingemann’s piece, Memories of Passersby I, for sale, making it the world’s second A.I.-generated artwork to go on the auction block.

Memories of Passersby I—an ever-changing stream of distorted, A.I.-generated human faces— sold for approximately $50,000. Klingemann likes to joke that Botto, his protégé, has made more money in less than two years than he’s made over several decades.

Birth of Botto

As Klingemann continued to make algorithmically produced art, he wondered whether it was possible to replace the human-generated parts of the process—the code that produces images, the ideas that inspire the code—with A.I.

And in 2018, after musing about a project where separate A.I. artists would compete against each other for human approval, he soon pivoted to what would become Botto: a composite system of A.I. algorithms that communicate with humans to create thousands of images every week.

Klingemann uses a language model, or A.I. algorithm that spits out text, to generate prompts. He feeds these prompts to two A.I. image generators (currently Stable Diffusion and VQGAN+CLIP), which produce an image. Every week, the algorithms generate between 4,000 to 8,000 images. Then, humans vote on their favorite work, and the votes in turn train Botto’s “taste model,” or A.I. algorithm that chooses what images to show each week. The winning image is then minted and sold to the highest bidder.

To incentivize a community to vote on Botto’s art, Klingemann, with the help of Web3 specialists, created a DAO, or a decentralized autonomous organization, which is common in crypto. To gain access to BottoDAO—currently with a market capitalization of nearly $4.7 million, according to CoinMarketCap—one must buy at least one “governance token” for approximately 17 cents. Those with more tokens have a greater say on which weekly image is minted as well as on what proposed changes to Botto are implemented.

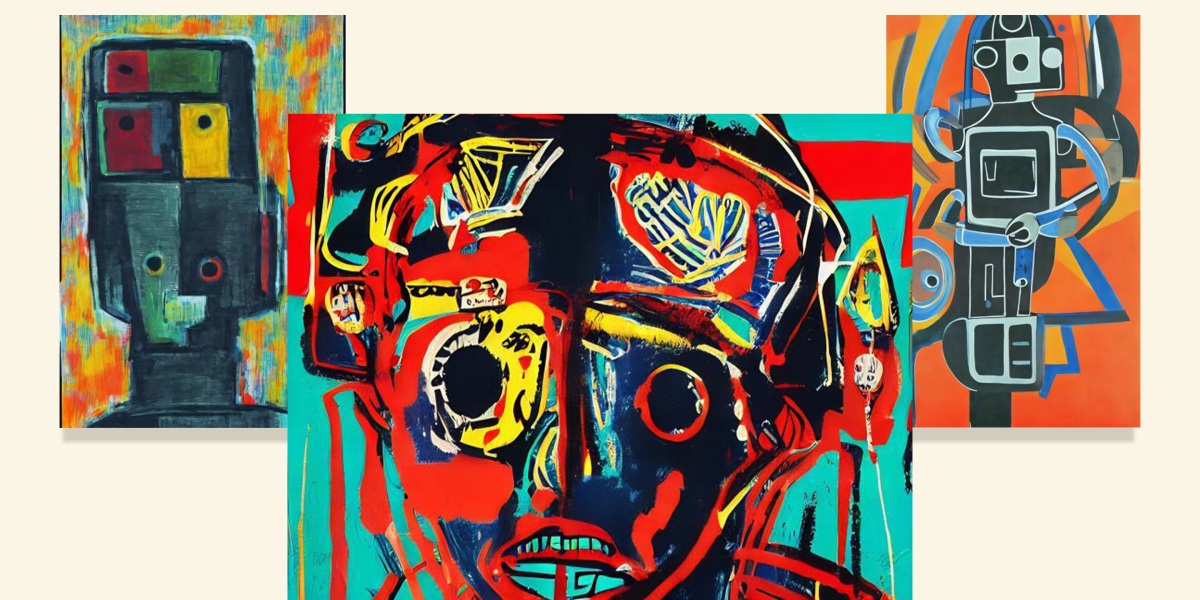

Courtesy of Botto

“Artists operate with feedback and are in discussion with their audiences all the time,” Simon Hudson, one of two full-time project leads in BottoDAO, said to Fortune. “Does that violate their agency? I don’t think so.”

Ultimately, the many turning wheels of Botto produce what, Klingemann, Hudson, and other members of the community call a “decentralized autonomous artist.”

“It’s trying to start with a sense of contained agency,” Hudson said. “And by contained, I mean, it’s a closed-loop system—there’s no human intervention in the creation of the art.”

Botto’s escape

After Botto officially launched in October 2021, it made a killing. Its first work, Asymmetrical Liberation, a tangled collection of abstract human figures, sold for approximately $325,000. Its next piece, Scene Precede, sold for even more—about $430,000.

This was near the height of the NFT craze, before the bottom of the market fell out as Crypto Winter wiped out billions of dollars in trading volume. From January to October 2022, total NFT trading volume decreased more than 90%, according to data from CryptoSlam.

Now, Botto’s work is selling for a fraction of what it was going for at its peak. Its most recent piece, for example, sold for a little less than $14,000. The waning revenue may spell trouble for the BottoDAO, which distributes half of those proceeds to all holders of the Botto token and the other half to the DAO’s treasury. Team members, including Hudson and Klingemann, are paid in Botto tokens, whose price depends on the perceived strength and profitability of the project.

“Is it low compared to the first few weeks of sales? Absolutely,” said Hudson, referring to recent bids on Botto’s art. But, he added, sales are still “strong and profitable,” specifying that the community has made approximately 64.5 ETH, or a little less than $120,000 in current prices, from pieces auctioned off in its most recent collection.

“It’s a reality of every artist,” Klingemann told Fortune. “You have to balance between doing the art you would love to do and doing the art that sells.”

Despite the broader market downturn, the German artist believes the future for Botto—still “an infant”—is full of possibilities. Perhaps the decentralized autonomous artist will become self-sufficient and upgrade itself without community approval? Or maybe, Klingemann ponders, Botto will produce “offspring” that divide and multiply like cells? Eventually, he says, “You have more and more instances, and Botto takes over the world.”

Let’s hope the decentralized autonomous artist looks fondly upon its predecessors.

[ad_2]

Source link