[ad_1]

This column is an opinion by Jonah Prousky, a management consultant based in Toronto, focusing on data, analytics and artificial intelligence. For more information about CBC’s Opinion section, please see the FAQ.

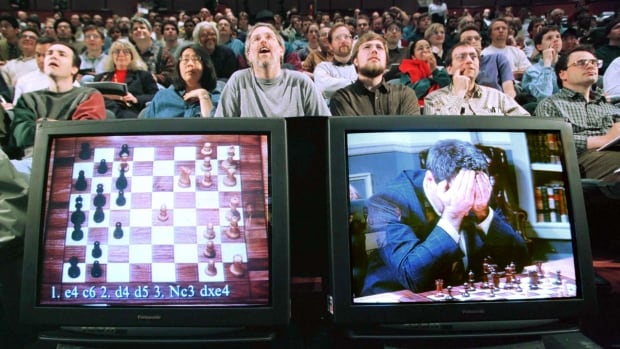

On May 12, 1997, the front page of the New York Times read, “Swift and Slashing, Computer Topples Kasparov.”

The article, for those who may not remember, broke the news about one of the most infamous chess matches of all time, in which an IBM supercomputer, Deep Blue, defeated reigning world chess champion Garry Kasparov in six games.

For many, this was far more than a chess match between man and machine. It was a sign that the gap was closing between artificial intelligence (AI) and human intelligence. And in a big way.

OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT will go down as another extraordinary encounter between man and machine. Only this time, it isn’t a game. Language and its infinite applications are at stake.

Not coincidentally, Garry Kasparov’s words when reflecting on his loss to Deep Blue 10 years later in an interview with the CBC seem most appropriate for this moment. “I always say, machines won’t make us obsolete,” he said. “Our complacency might.”

And while it doesn’t look like ChatGPT will in fact make us obsolete, it has provided us with a sobering reminder of AI’s potential to disrupt many aspects of the human experience: education, medicine, law, commerce, and everything in between.

In response, we need to be mindful of Kasparov’s words and fight our tendency toward complacency. We, most notably our politicians, need to manage the future of AI, not vice versa.

A regulatory conundrum

Members of the House of Commons are currently mulling over Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, which includes what could become Canada’s first piece of AI legislation, the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA).

If passed, the AIDA would place several guardrails on the uses of AI and enforce penalties for noncompliance up to $25 million.

This is certainly a step in the right direction, though it’s easy to foresee several challenges the AIDA or any policy like it will face when enacted.

Firstly, technology develops exponentially, but the legislative process is linear, where bills plod through the House and Senate before being passed into law. It might be many months or years before AI legislation is passed, yet it’s difficult to predict what AI will be capable of at that point.

Managing risks that grow exponentially has been acutely challenging in the past. Consider how badly COVID-19, which came in exponential spikes, stressed hospital capacity and other essential services.

I think that’s the speed at which AI will spread as the technology improves. It took less than one week for ChatGPT to amass over one million users. What’s more, the next, more powerful iteration of the software has already been announced by OpenAI.

Secondly, AIDA is chiefly concerned with uses of AI that are deliberately harmful, such as data privacy breaches or financial crime. But it’s the grey zones that are more concerning. In education, for example, some have posited that this new step forward in AI will make homework a thing of the past. But will that make the next generation of students more or less intelligent?

Zoom out, and many of the applications of AI — in social media, or national defence, perhaps — start to look the same way. That is, they may not be deliberately harmful but their net effect on society is largely unknown.

Thirdly, corporations will ultimately own this technology and that has the potential to be both a blessing and a curse.

Microsoft is poised to invest an additional $10 billion in OpenAI and, like any corporation, will have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize profits for its shareholders. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Consider how quickly corporations developed and distributed vaccines for COVID-19. The incentive to use AI to turn a profit may lead to the next breakthrough in science or medicine.

However, when corporate and social interests are at odds, corporations have a funny way of getting what they want — usually through effective government lobbying. If there are profitable applications of AI that are detrimental to society, AI legislation alone might not be enough to stop them.

The path forward

Canada’s proposed AI legislation is lenient enough to allow for a future where many aspects of human life are augmented by AI. The technology is arguably in its infancy, yet already capable of carrying out highly nuanced tasks such as weeding through job applications, predicting verdicts in legal trials or diagnosing sick patients.

It will be fascinating to watch regulators ponder the ethical boundaries of life with AI, and nobody knows exactly how this will play out.

In the years that followed Kasparov’s defeat, Deep Blue’s successors, such as Google’s AlphaGo, got a lot more powerful. But what people tend to forget is that the technology made human chess players better as well.

AI didn’t make chess obsolete. In fact, it made the game more interesting.

ChatGPT has many flaws. It struggles a bit with ambiguity, and it has a so-far-amusing tendency to present false information as fact. In that sense, ChatGPT looks more like the Deep Blue from Kasparov’s first bout with it in 1996, where Kasparov came out ahead four games to two.

If history repeats itself, ChatGPT and its successors will continue to improve and encroach on many aspects of human intelligence. Along the way, things will get a lot more interesting.

Our job, as Garry Kasparov reminded us, will be to guard against complacency.

Do you have a strong opinion that could add insight, illuminate an issue in the news, or change how people think about an issue? We want to hear from you. Here’s how to pitch to us.

[ad_2]

Source link