[ad_1]

With the semester nearing its end and the standoff between the Graduate Employees’ Organization and the University of Michigan raging on, there’s no better time than now to reflect back on how this school year has gone academically. For some, this year was filled with packed schedules, long study nights and never-ending amounts of work; for others, classes may have been an afterthought. Personally, I tried to find a middle ground: balancing a moderate course load with time to socialize. Regardless of how the year played out for you, what unites many U-M students’ experiences is a general feeling that the traditional way we learn has changed.

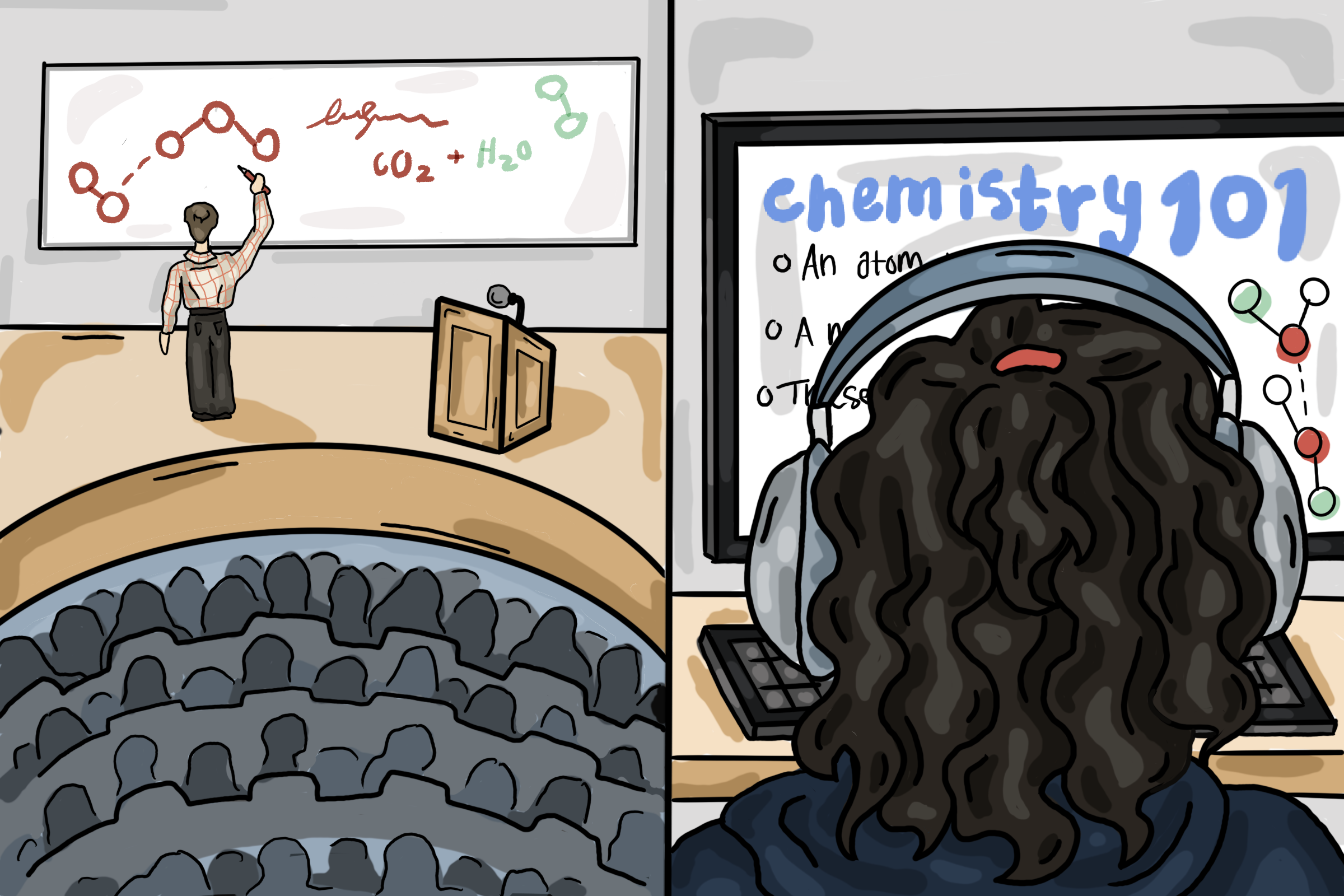

It is important to first define the traditional way we learn at the University of Michigan. This idea refers to the lecture and discussion format that makes up the overwhelming majority of courses provided by the University. These are the classes where students have the opportunity to take part in both a large learning environment and a closer, conversational section. This structure is largely the norm.

The first major problem with this system has to do with attendance. While some courses make attendance in lecture compulsory, there are many where that is not the case. Scores of students skip their lectures, choosing to spend their time sleeping in or socializing rather than learning from their professors. For example, in an astronomy lecture of mine, only 10 students showed up when more than 100 were registered. It appears that as of late, students are not showing up to class in the same capacity they have in the past.

Why, you might be asking, has this become so widespread? The simplest answer is laziness. It’s much easier for a busy college student to stay in the comfort of their own home than to walk 10 minutes to a lecture hall. Furthermore, with the rise in Lecture Capture spearheaded by the pandemic, there are many students who prefer to watch lectures on their own time rather than attending them in-person. But laziness cannot be the sole reason why students skip lectures, especially when our coursework and extracurriculars become more strenuous over time. There must be something greater at play here, something that can be better understood if we consider the changing ways U-M students complete their schoolwork.

The days when completing schoolwork was a strictly human process are over. When tasked with essays to write, worksheets to fill out or projects to work through, many students are not turning to their lecture notes, textbooks or even the internet for help. They are looking to their pal ChatGPT and other Artificial Intelligence softwares to get the work done for them. One in five college students have turned to AI tools in order to complete their assignments, and this figure will only be exacerbated if the traditional learning system remains stagnant while AI continues to innovate.

It is the digital age that is leading traditional college classes down the path to antiquity. This explanation, though, is only half the story. The problem has much more to do with the way technology has impacted human behavior than it has to do with the technology itself.

For starters, convenience has become the name of the game. With just a few clicks on a screen, we can buy anything we want, talk to whoever we want and practically see or hear anything we want at a moment’s notice. Students will turn to ChatGPT to complete their assignments for the same reason millions of people use Amazon each day to shop: They want things to be quick and easy. If this is what people desire for practically every other facet of daily life, why should education be any different?

On a similar note, technology has led to a growing desire for personalization. We personalize our phones with applications that are tailored to our personal preferences and needs. We carefully watch videos on TikTok so that our For You pages are customized to our interests. More than 70% of consumers expect companies to deliver personalized interactions, and students want the same from their education. In the busy lives of college students, it is much more attractive to be able to customize learning by fitting lectures into their own schedule than it is for students to have to abide by a fixed learning environment.

The digital age has transformed the desires of college students, leading them to emphasize convenience and individuality in the educational process. It may be too late to stop this growing sentiment among students, but it is not too late to question whether or not these changes are good for our education. For some, the growing obsolescence of the traditional college class may represent a loss of connectedness and organization in the learning process. For others, it might feel like a step in the right direction toward an education system that sees students as individuals and not as small cogs in a larger machine. Regardless of how you see it now, it will be the next generations of students that will contend with these changes, and I can only hope that the University of Michigan will be a leader in the digitization of education in the years to come.

Max Feldman is an Opinion Columnist who writes about the underappreciated and infrequently discussed aspects of University of Michigan culture. He can be reached at [email protected]

Related articles

[ad_2]

Source link